Frequency-dependent selection as a mechanism maintaining the genetically based variation in male guppy colouration

Frequency-dependent selection as a mechanism maintaining the genetically based variation in male guppy colouration

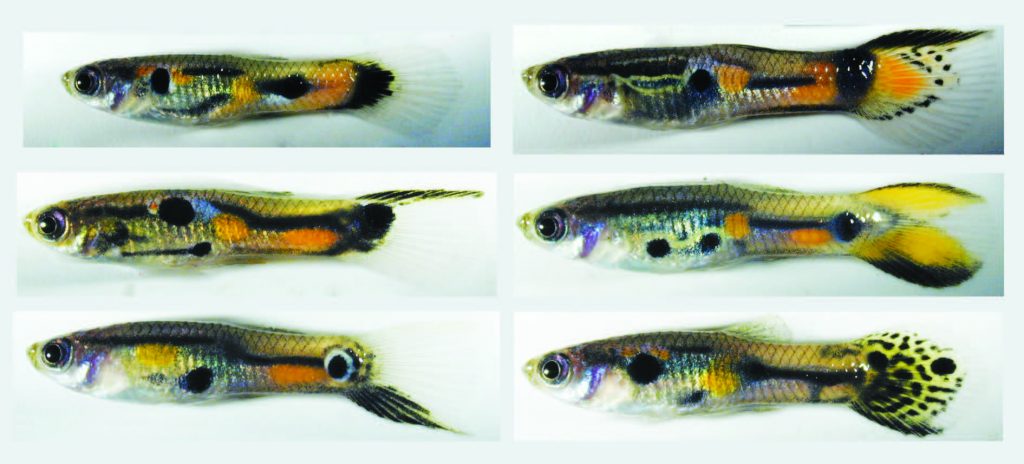

Wild guppies (Poecilia reticulata) exhibit one of the most striking examples of genetic polymorphism among animals. In local populations, there may be almost as many different male colour patterns as there are males, yet colour pattern is genetically determined. Previous work suggests that rare or novel males have an advantage in attracting mates and avoiding predators, possibly leading to negative frequency-dependent selection.

Another hypothesis consistent with these results is that males that are similar or identical to other males in colour pattern are at a disadvantage due to “redundancy” (as opposed to an advantage of rarity) of their pattern. Using a combination of field and laboratory studies, we are testing for frequency-dependent mating and survival advantages that could maintain genetic variation in male colour pattern. We have found that males with rare colour patterns do indeed have a survival advantage (Olendorf et al. 2006); one of our goals is to examine factor(s) that could contribute to this advantage: does it have to do with the predator’s attack strategy? with the mate searching strategies of male guppies?

Collaborators: Kim Hughes, Florida State University Anne Houde,Lake Forest College (see Anne's webpage for information about her excellent book on guppies)

Publications:

Hughes, K.A., A.E. Houde, A.C. Price, F.H. Rodd. 2013. Mating advantage for rare males in wild guppy populations. Nature 503:108-110 10.1038/nature12717

Olendorf, R & F.H. Rodd, D. Punzalan, A.E. Houde, C. Hurt, D.N. Reznick & K.A. Hughes. 2006. Frequency-dependent survival in natural guppy populations. Nature 441: 633-636

Hughes, K.A., F.H. Rodd and D.N. Reznick. 2005. Genetic and environmental effects on secondary sex traits in guppies (Poecilia reticulata). Journal of Evolutionary Biology 18: 34-45

Hughes, K.A., L. Du, F.H. Rodd and D.N. Reznick. 1999. Familiarity leads to female mate preference for novel males in the guppy, Poecilia reticulata. Animal Behaviour 58: 907-916

Sensory bias in poeciliids

Most female guppies (Poecilia reticulata) prefer males with large, bright orange spots (Endler & Houde 1995). This preference can provide females with information about the quality of potential mates (e.g. parasite load, sperm number) (Houde 1997, Pitcher 2005). However, our studies suggest that this preference originally arose as a sensory bias for orange in a foraging context—male and female guppies forage on orange-coloured foods (e.g. fruit) and are attracted to orange outside a mating context (i.e. to orange-painted disks) (Rodd et al. 2002).

Indeed the strength of female preference for orange spots on males is tightly correlated, across populations, with the number of times females in these populations peck orange-coloured disks (Rodd et al. 2002, Grether et al. 2005).

Recently, my former co-advised MSc student, Michael Foisy, in collaboration with Luke Mahler, used male colouration, a phylogenetic approach, and experimental colour preference tests to determine whether a sensory bias for orange, red and yellow (long wavelength colours) is widespread among 200+ species related to guppies (poeciliids (including mollies, swordtails), goodeids, and medaka). We found that a large proportion of males of these species have long wavelength colouration and that the model predicted that a sensory bias for these colours would be widespread. Michael and our colleagues then tested these predictions by testing 20 species for their colour preferences—almost all of them were correct!

Recently, my former co-advised MSc student, Michael Foisy, in collaboration with Luke Mahler, used male colouration, a phylogenetic approach, and experimental colour preference tests to determine whether a sensory bias for orange, red and yellow (long wavelength colours) is widespread among 200+ species related to guppies (poeciliids (including mollies, swordtails), goodeids, and medaka). We found that a large proportion of males of these species have long wavelength colouration and that the model predicted that a sensory bias for these colours would be widespread. Michael and our colleagues then tested these predictions by testing 20 species for their colour preferences—almost all of them were correct!

Painting by Viviana Astudillo-Calvijo of one of the poeciliids, Limia vittata, included in the study mentioned above.

Next steps can include expanding our assessments of the colouration and colour preferences of more fish species in mating and non-mating contexts. This includes adding artificial stripes to species without colour patterns but predicted to have a mate choice preference for long wavelength colours, and assessing aspects of the habitat that could influence signal (male colouration) efficiency (e.g. water colour, turbidity, habitat complexity, substrate colour (Endler 1992)) in natural populations.

Other future directions could include asking: did the female guppy mate choice preference for orange spots on males arisen as a by-product of natural selection on foraging for orange-coloured, carotenoid-rich fruit? Here are some approaches available to answer this question:

- Do the among-population differences in the strength of female preference for orange spots on males result from differences in their vision?

- If there are differences in their vision, is it because of general ambient colour characteristics of their habitat and/or because of differences in food resources available to them? We have started to investigate this question using stable isotopes to identify the food resources that guppies are consuming in natural populations.

Collaborators:

Michael Foisy, U of T

Luke Mahler, U of T Anna Price, U of Toronto Margaret Ptacek, Clemson University Shala Hankison, Clemson University Greg Grether, UCLA Gita Kolluru, CalPoly

Publications: Grether, G. F. Kolluru, G.R. Rodd, F.H. De La Cerda, J. Shimazaki, K. 2005. Carotenoid availability affects the development of a colour-based mate preference and the sensory bias to which it is genetically linked. Proc. R. Soc. B. 272: 2181-2188(pdf) Rodd, F.H., K.A. Hughes, G. Grether, C.T. Baril. 2002. A possible non-sexual origin of a mate preference: are male guppies mimicking fruit? Proc. R. Soc. B. 269:475-481(pdf)

Plasticity in life history traits and behaviour

I also have an interest in phenotypic plasticity in reproductive strategies: life history traits and sexual behaviour. We study the ways in which individuals adjust their reproductive strategies in response to the behaviour and population demography (e.g., sex ratio, density) of conspecifics, to predation risk, and whether those strategies are adaptive. For example, female H. formosa, another livebearing poeciliid, provide nutrients to their offspring throughout development and, in some populations, this species lives at extremely high densities. Do females of this species, as theory predicts, produce larger offspring at higher densities? And if so, what are the advantages of a larger size at birth?

Collaborators on the Heterandria formosa project on plasticity in offspring size in response to population density: Joe Travis, Florida State University Jeff Leips, UMBC

Publications: Gosline, A.K. and F.H. Rodd. 2007. Predator-induced plasticity in guppy (Poecilia reticulata) life history traits. Aquatic Ecology. DOI 10.1007/s10452-007-9138-7(pdf) Rodd, F.H., D.N. Reznick and M.B. Sokolowski. 1997. Phenotypic plasticity in the life history traits of guppies: response to social environment. Ecology 78:419-433(pdf) Rodd, F.H. and M.B. Sokolowski. 1995. Complex origins of variation in the sexual behaviour of male Trinidadian guppies (Poecilia reticulata):interactions among social environment, heredity, body size, and age. Animal Behaviour 49:1139-1159 pdf)